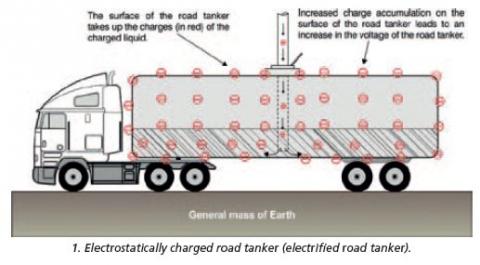

As the product (liquid or powder) moves through the transfer system and interacts with pumps, valve, filters, meshes and pipe walls, the product will be building up the amount of electrostatic charge it carries. In electrical terms this is commonly described as static charge accumulation. When the product is transferred into the road tanker, the road tanker, will in turn, become electrified and be subjected to a rising voltage.

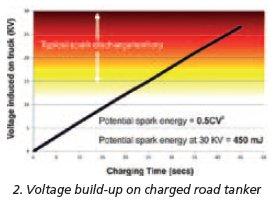

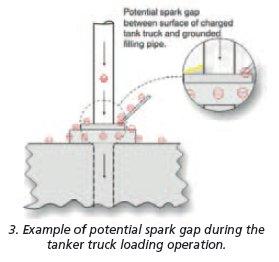

For example, a typical road tanker when it is being filled with a liquid at recommended flow rates, but is without static earthing* protection, could have its voltage raised to between 10,000 volts and 30,000 volts within 15 to 50 seconds. This voltage range is very capable of discharging a high energy electrostatic spark towards objects at a lower voltage potential, especially anything at earth potential. Examples of objects at earth potential could be operators working in the vicinity of the road tanker or the filling pipe situated in the hatch on top of the road tanker.

It is possible to estimate the energy of such sparks by combining the capacitance of the road tanker with the voltage present on the road tanker. The capacitance is a measure of how much charge can accumulate on the outer surface of the road tanker. Because road tankers have a very large surface area, they can accumulate very large amounts of charge, which in turn, creates the presence of very high voltages on the surface of the road tanker.

For example, a truck with a capacitance of 1000 pico-farads that is electrified to 30,000 volts has 450 milli-joules of potential spark energy. Given that most hydrocarbon vapours and gases have MIEs of less than 1 milli-joule and most combustible dusts have MIEs of less than 200 milli-joules, it’s easy to see why road tankers that do not have static grounding protection in place can be a major ignition source in a hazardous area.

To counteract this risk, it is important to ensure that the road tanker does not have the capacity to accumulate static electricity. The most practical and comprehensive way of achieving this is to make sure that the road tanker is at earth potential, especially before the transfer process starts. When we describe “earth potential” we mean that the road tanker is connected to the general mass of the Earth, which is commonly referred to, in electrical terms as “True Earth”.

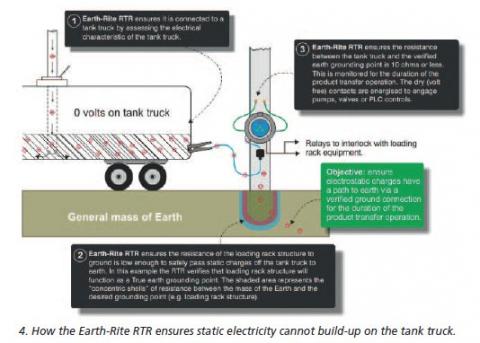

This is because the general mass of the Earth has an infinite capacity to pull static charges from the road tanker, which in turn eliminates the generation and presence of voltages on the road tanker. The Earth-Rite RTR performs three critical functions which ensure the fire and explosion risk of an ignition caused by static electricity is eliminated. The first function the RTR performs is in determining if the driver or operator has made a secure connection to the body of the road tanker.

This minimises the risk of the driver obtaining a permissive condition for the earthing system by connecting to objects like the loading gantry, or objects on the road tanker that could be isolated from the main body of the road tanker as this would defeat the objective of passing electrostatic charges from the road tanker to earth.

The RTR then verifies if it has a low resistance connection to True Earth via the structure to which it is connected, e.g. the loading gantry. As any static charges generated by road tanker loading (unloading) process will travel to earth via the RTR, it is important to ensure the RTR itself has a low resistance connection to earth. When both of these conditions are positive,

i.e.:

1. The RTR knows it is connected to a road tanker.

2. The RTR knows it is connected to a verified earth ground.

10 ohms is the benchmark requirement repeated in several international standards,the most prominent of which is the IEC 60079-32 standard and the American NFPA 77 “Recommended Practice on Static Electricity”.

If the resistance is not more than 10 ohms the RTR will verify that the road tanker is connected to earth and indicate this via its ground status indicators, a cluster of green LEDs that pulse continuously.

* “earthing”: the equivalent term is “grounding”.

The RTR will then establish if the connection resistance between the tank truck and the verified earth ground is 10 ohms or less. 10 ohms is the benchmark requirement repeated in several international standards, the most prominent of which is the American NFPA 77 “Recommended Practice on Static Electricity” and Europe’s IEC 60079-32 standard. If the resistance is not more than 10 ohms the RTR will indicate that the tank truck is connected to ground and indicate this via its ground status indicators, a cluster of green LEDs that pulse continuously.

The reason the LEDs pulse is to indicate that the RTR is continuously monitoring the static earthing circuit between the road tanker and the verified earth point for the duration of the loading (unloading) process. If the resistance of the road tanker’s connection to the verified earth (e.g. loading gantry) ever rises above 10 ohms, the RTR will go non-permissive.

Both of the standards listed above recommend that interlocks controlling the flow of product to or from the road tanker are provided by the earthing system. To comply with this requirement, the RTR has two volt free contacts that can interface with control circuits for pumps, valves and PLCs.

If the RTR determines that the road tanker has lost its connection to earth, the volt free contacts can be used to halt the transfer process. The benefit of halting the transfer process removes the charging mechanism that would otherwise charge up the road tanker while it has no active static earthing protection in place.